I’m thinking I’ll move away from Embarrassing Personal Storytime for a while, but this post is nonetheless about a creator of early personal significance to me. I’ll be focusing a whole lot more on the artist himself, though, which I’m sure his dead self will appreciate.

___________________

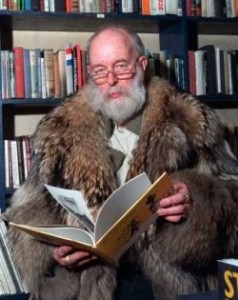

Edward Gorey was one in a long tradition of (at least vaguely) queer or non-heteronormative eccentric creative producers and aesthetes, but one in a relatively less popular mold. He wore an enormous fur coat, sneakers, a substantial beard and a great many large rings on his fingers, and never hid his non-normative aspects, at a time when such things faced more substantial social sanction than they do now. He clearly took some enjoyment in his own person, saying in a 1980 interview for Boston Magazine (included in the excellent Gorey interview collection Ascending Peculiarity) that “part of me is genuinely eccentric, part of me is a bit of a put-on.” Yet, unlike a Quentin Crisp type, he did not seek attention in the media, and claimed a great distaste for interviews, consenting to the fairly substantial number that he did only out of kindness. He was open about his asexuality, describing himself in the same interview as “reasonably undersexed” – yet, not being Oscar Wilde or Allen Ginsberg, never romanticized it or treated it very directly in his work. His life was extremely ritualized, but not having the taste for melodramatic pomp and ceremony that Aleister Crowley had, his rituals consisted of formalized daily habits, some of them quite “ordinary” and domestic. He was extremely well-read and quite literary in character, but was not in the mold of a Judith Butler, and so hid his erudite intertextuality beneath the surface of his works instead of making it the surface. In short, he was a sort of private flamboyant, like the goth kid at the club who’s wearing the boldest and most unusual outfit on the dance floor, and yet spends most of their evening in a corner, saying nothing to anyone and minding their own business – there, unlike those taking up the floor’s center, precisely not to be seen.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Edward Gorey and the enormous, very soft dead animal in which he loved to wrap himself

This quietness of sorts, not blending in and yet blending in, being visible and yet secluded, I think creates a substantial portion of his appeal. It also allows him to be widely likeable and accessible, grokked on one level or another by various sorts of people: in one interview, he recounts being told about how someone’s small child was a great fan of his ostensibly (though not explicitly) pornographic book, The Curious Sofa. His works have been appreciated by children at the same time that they were being lauded by literary critics and acclaimed by Max Ernst. Gorey had great interest in Surrealist theories of art, and frequently betrayed in his work philosophical sentiments in line with Big Ideas of the time, such as Existentialism and Absurdism. He ventured into the realm of modern experiment: a book starring a series of interior environments, objects and the occasional human being, but no recurring characters and no words (The West Wing), a book in which the characters are inanimate objects (The Inanimate Tragedy), and one in which the main subject is never seen in-frame (The Sinking Spell). These, too, might be appreciated by children. In fact, Gorey’s work seems to point up the extent to which the manner in which creative work is regarded is dependent on the cultural framework in which it is set – mightn’t Ernst’s Une Semaine de Bonte and various of his paintings be enjoyed by the same sort of precocious, morbidly-inclined and imaginative children? I’d venture that the right kind of child would enjoy the parental-queasiness-inducing nudity and eroticism of Une Semaine de Bonte more than many adults would.

Gorey spoke of preferring a fairly unplanned, direct mode of creative production, and his work has a whole lot of his own character in it, in its implied asexuality, ritual repetition (a big deal for him – he attended every single performance of the New York City Ballet for many years), habitual return to themes, cycling cast of motifs, character types and plot tropes, and so on. One of these tropes – that of sudden appearance and sudden, inexplicable change – is of particular interest to me, and I’d like to discuss it further.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

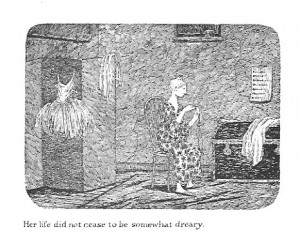

The dreary life of Maudie Splaytoes, icon of the age and ballerina by rather coercive chance

One incarnation of this trope is in The Lost Lions: Hamish, a “beautiful young man who liked being out of doors,” opens “the wrong envelope” and ends up becoming a famous actor. No further explanation is provided for the envelope; it simply arrives, is opened, and suddenly Hamish’s life changes. In some ways, it is substantially similar to how it would have been otherwise – in the films, he is “almost always out of doors.” He eventually stresses out, flees, but then returns to his remarkable-and-yet-unremarkable life and to the story’s non-ending. In The Gilded Bat, the envelope is replaced by a living Other: a Madame who carries little Maudie Splaytoes off to learn dancing and live the life of a ballerina. The Madame “inform[s] the Splaytoes that the child [is] to be her pupil”; neither they nor Maudie seems to have a say in the matter. She goes through long years of training and study, and “her life [is] rather monotonous.” She goes through the Madame being “removed to a private lunatic asylum, and the school… shut down,” finds a place in a ballet company, dances her first solo roles, and “her life [goes] on being fairly tedious.” She joins the most renowned company in Europe, and “her life [does] not cease to be somewhat dreary.” She dances in great starring roles, develops a lover in one of the other dancers, has a ballet created for her by a (presumably) great choreographer (it’s his greatest work), endures the lover’s removal to a sanatorium, “all at once [becomes] chic and mysterious,” and becomes “the reigning ballerina of the age, and one of its symbols.” Her life is “really no different from what it had ever been” ; finally, a bird flies into her aeroplane, and she dies as suddenly as her life as a ballerina had started.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

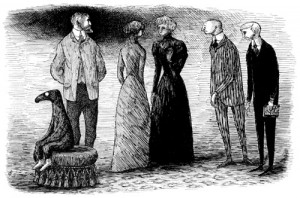

The Doubtful Guest existing in its bubble, amongst but apart from its family

In The Sinking Spell, the entire book is devoted to the arrival in, and descent through, an old vaguely Victorian house of some great Other that is neither named nor shown in frame. It is thus defined completely in terms of its Otherness, an unknown form that the family and their maid is seen again and again staring at, and yet is never seen by the reader, who only knows it exists through the gaze of the family and the voice of the narrator. The Doubtful Guest, one of the best-known Gorey stories, is the same narrative, but with an Other who is visible, and who stays. A black, round-eyed and beaky humanoid figure in a scarf and sneakers shows up at the house, and promptly settles into a routine of destroying the family’s possessions, eating their food, having wrathful fits, nighttime tiptoeing, and laying on the floor (in the way, of course) every Sunday. As of the end of the story, it has been in the house for seventeen years – “and to this day, it has shown no intention of going away.” Unlike the family in The Sinking Spell or Hamish in The Lost Lions, The Doubtful Guest’s family seems quite angry at the Guest’s actions – and yet they make no attempt to remove the Guest from their home. The Other becomes familiar, but remains incomprehensible. The Doubtful Guest seems identifiably to be a metaphor for a child, albeit not of the kind that usually serve as woeful cannon fodder in Gorey’s tales.

The sudden appearance of a companion entity (as in The Doubtful Guest and The Sinking Spell) occurs in combination with sudden change of vocation in which the character has no say (as in The Lost Lions and The Gilded Bat) in The Disrespectful Summons. The Devil happens upon Miss Squill, kicks her and whirls her about; when she returns home, she find his mark burnt upon her breast, and the “next day [flies] in her open door a creature named Beelphoazoar,” presumably of demonic extraction. The creature teaches Miss Squill to do evil things, like cindering toast and rotting silk, and sleeps on her bed with her; eventually, the Devil arrives again to pull her down to Hell. Once again, this same story takes a different form in The Osbick Bird, perhaps my favorite Gorey tale of all. One day, a gentleman by the name of Emblus receives a visit: “An osbick bird flew down and sat on Emblus Fingby’s bowler hat. It had not done so for a whim, but meant to come and live with him.” Fingby, like Gorey himself, leads a ritualized and habitual life, and simply accepts the bird into that life, so that the bird becomes his constant companion. They play flute and lute together, have tea and go walking, driving and canoeing, have spats, wear matching boots, and pass time with hobbies. Emblus finally dies, and the bird, at first sitting vigil upon his headstone, eventually flies away.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The Osbick Bird makes its sudden appearance

There is a substantial non-gender-normative and (broadly) queer aspect to these suddenly appearing companions, simply accepted into the characters’ habitual and cyclic daily lives. The Sinking Spell entity, the Doubtful Guest, Beelphoazoar and the Osbick Bird are all without gendered signifiers; all four are referred to as “it.” The Spell entity, the Guest and Beelphoazoar, though, have fairly definable relationships with the humans in their environments (haunting ghost or possessive entity, child and possessive demon/companion spirit, respectively), whereas the Osbick Bird does not. Are Emblus Fingby and the Bird asexual romantic partners? They could be, certainly; they watch the sunset together, go on journeys in what could be seen as romantic settings, and have spats; of course, all of the things in the story are within the bounds of close friendship. Are they sexual together? Maybe (and maybe this is the case with Miss Squill and Beelphoazoar, too, as they’re seen sharing the same bed). It is certainly a very queer relationship, and carries some of the feel of a Boston marriage, such as those that occurred between women in the 1800s who were supposed to be close, non-sexual romantic friends.

Existential absurdity and meaninglessness certainly abound in these and other Edward Gorey stories, but there is never any great existential drama, any opening up to the absolute, terrifying freedom of life. Instead, characters seem to move along in life in the same patterns as always, unless reprogrammed by some external force; absurdity happens to them, but they don’t appear to really grapple with it. Of course, in the same way that Gorey was never really just a creator of alphabet books, (at least some of) his characters may not really be asleep.